And then there were other faces. The faces of nations,

Governments, parliaments, societies,

The faceless faces of important men.

It is these men I mind:

They are so jealous of anything that is not flat! They are jealous gods

That would have the whole world flat because they are.

— Sylvia Plath, “Three Women: A Poem for Three Voices”

NB: The following document was discovered in the possession of Chief Investigator Barney Kane after his recent passing. Given the author’s obvious mental disturbance, not all claims herein are verifiable; nevertheless, the past month’s revelations regarding several of the persons identified by the author render its publication imperative. Other than the correction of spelling and grammatical errors and the changing of names to protect the innocent, the document is published as written. Rumors that the author is alive and living under an assumed name in Spain can be neither confirmed nor denied.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: As my notes on the information herein were destroyed, I am working exclusively from remembered fragments, which may not be strictly accurate. — L.C.

Not much time remains. In a matter of hours I shall be executed, made an example of for any other innocent so foolish to follow my path and discover this most dreadful of conspiracies. While I may die, this confession-cum-expose will hopefully allow the world to know the truth behind our history and ensure my early demise shall not be in vain. I understand, naturally, that this confession will likely be destroyed, and even if it survives few shall believe it. This does not matter to me: the dead man walking is still walking, and he can also write, and so long as he can purge his pathetic mind of its sins he shall find absolution before eternity swallows him whole.

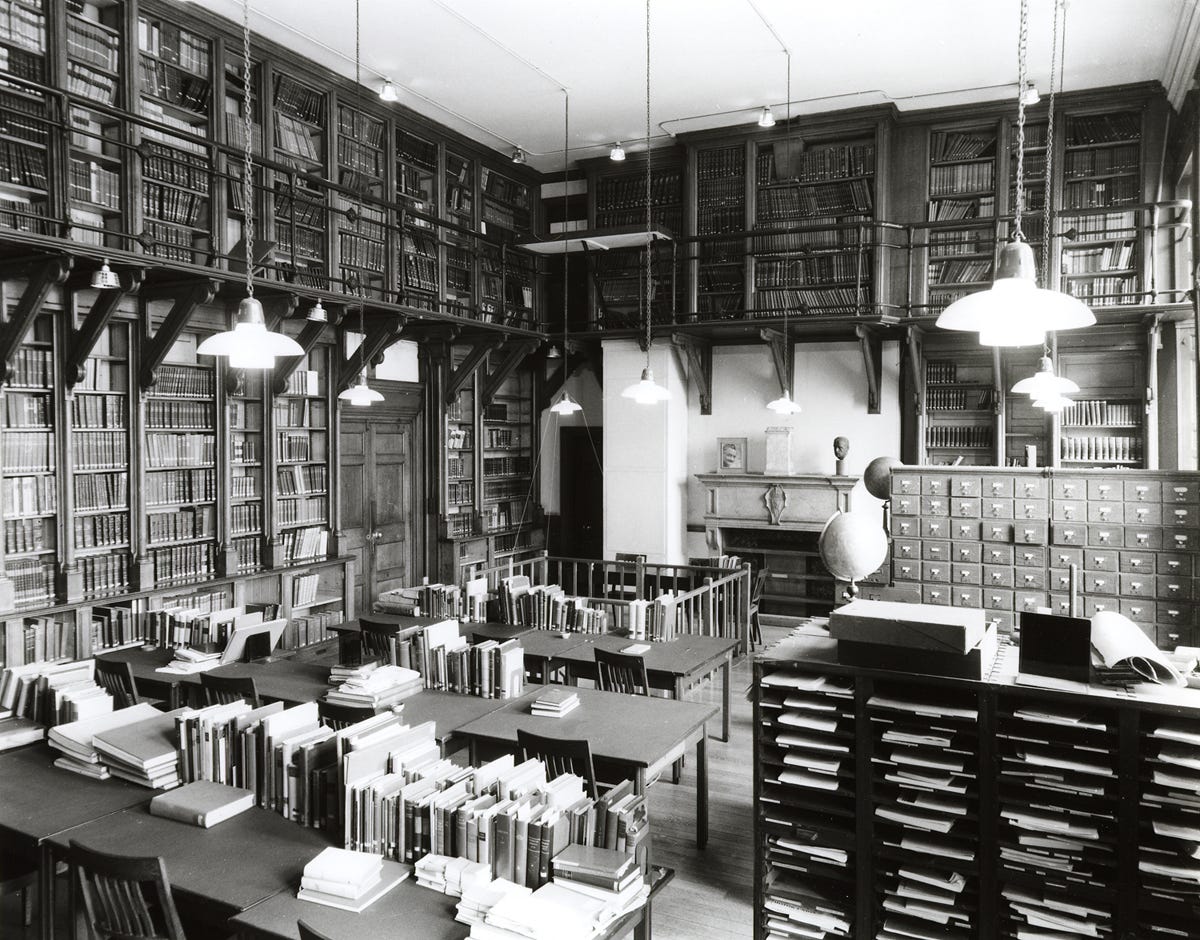

My name is Linus Carlyle, and I was a history student at a prestigious university whose identity I will not disclose (but which is obvious to the educated reader). I come from a relatively modest and provincial background: I hail from the bourgeoisie of a drab Midwestern city which is neither large nor small and contains nothing interesting. While most of my peers led lives of privileged idleness, I — owing to my region and class’ crippling practicality —chose to work in college (despite having no financial need to do so) to ward off dissolution and sloth. I thus obtained a job in the college library’s special collections, which consisted of little besides sorting through old papers and fulfilling the requests of scatter-brained academics, doddering old ladies, and overtaxed graduate students. It was unglamorous and largely boring and I cursed the idlers with their Sag Harbor summer homes and glamorous European vacations while I ran manila folders to some sociology professor who would get lost in a brown paper bag.

One rainy, humid Monday afternoon, I was tasked with reorganizing the personal papers of one C. Hamlet Cheyney, a paper manufacturer in the opening decades of the past century. While Cheyney was not an industrial titan of the first rank, he was certainly acquainted with the Fricks and Fords and his firm produced official government stationery and documents during the Taft and Wilson administrations. Amid the numerous dull missives to various associates and now-obscure businessmen and politicians, one might also discover personal letters from F.D.R. on official Navy stationary or love notes to now-unknown starlets. In the course of my work I happened upon a letter embossed with a strange symbol which resembled two naked women facing each other, entwined like the snakes on Mercury’s staff. Jocularly addressed to “Hammy,” the letter began with the bland pleasantries typical of these things but got progressively stranger in the second paragraph; I presumed the symbol signaled some kind of erotic content (although the often embarrassingly explicit mash notes to the actresses were embossed with no such symbol) but this was evidently not so. There were cryptic references to “the ancient and holy rites held dear to our order” and “those of the opposite faith who as you read this entrench themselves ever deeper into the Republic’s governing apparatus” as well as a request to “congratulate Stillman on driving our ancient foe Vanderlip from the City Bank.” The letter was signed simply “Him.”

My mind reeled; in this big box of barely categorized memoranda and telegrams from a forgotten, minor plutocrat was something so cryptic and oddly disturbing that it shook me to my very core. My mind swarmed with questions: What rites and faiths? Why did the sender not identify himself? Who the hell are Stillman and Vanderlip? I glanced back at the embossment, puzzling over the feminine forms there. They seemed vaguely familiar and yet completely foreign to me. Where had I seen them before?

A memory flashed across my mind like a thunderbolt: last fall, I carried on a brief relationship with Cynthia, a friendly-but-snobby Southern blonde with an affected love for pickups and country and a tacky exurban house. I recall her wearing a necklace with a pendant depicting two nude women facing away from another, their backs touching. She claimed to not know the exact meaning, informing me it was a family heirloom and she found it “pretty.” While the romance died (a library rat and business major make a poor pairing), the necklace maintained its strange allure: what on earth did it symbolize? It was clearly antique and she obviously wore it out of family loyalty more than fashion sense. I still had Cynthia's number and wished to ask her about the necklace, but a small interior voice told me not to. For that one brief moment, my conscience won out. It would be its final victory in this life.

The next day, I doubled down on my journey to find out what, exactly, was going on with Chenyney and his entourage. There were boxes upon boxes of disorganized papers, shoved into creased folders with random, sometimes overlapping years scrawled on the labels — I counted three separate folders for “August 1912” — with a large number totally uncategorized. I paged through ledgers of illegible and unimportant sums and mash notes of the most embarrassingly erotic sort, stopping only to fulfill requests; the awful weather fortunately shrank the number of researchers to a skeleton crew, and my coworkers were so absorbed in their own duties that I felt secure tunneling down this rabbit hole in relative safety. None of the letters featured the aforementioned embossment, and I figured either they existed and Cheyney ordered them destroyed post-mortem or there truly was only that single letter, written for God knows what reason. I despaired, worried that my sacred Midwestern propriety had drowned in a flood of paper and paranoia.

Reaching the final box, I noticed a large brown book resembling a Bible, covered in a thick layer of white-gray dust which exploded in a noxious cloud when I opened it. The yolk-colored title page contained the words A HISTORY OF THE TWIN CULTS: FIFTH EDITION, LONDON 1922 in tall, blood-red Gothic letters. My stomach tightened: I knew what lay within these pages was awful in some ineffable way, something which would crack the thin shell between the world we know and the churning world beneath, the true, terrible world that moves everything above it like tectonic plates gliding along seas of liquid fire. I would spend a week in hell with this tome, a compendium of terrors which doubles as my gravestone: Here lies Linus Carlyle, reads its mocking epitaph, curiosity outright slaughtered this cat.

The History — which was written anonymously — is a rather dispassionate work; as the author says in the introduction:

I was born into one of these cults, and switched allegiance in young adulthood; but my allegiance was not strong enough, and I abandoned that one as well. I have subsequently become skeptical of all human good and all forms of belief…I have compiled this work as an internal record for both cults so they may learn more of one another, and eventually set their ancient hatreds aside and come together in spiritual harmony (although I know that the use of this book for nefarious ends is far more likely). That I have not been killed because of this endeavour stems solely from the protection of prominent figures within the cults…

The shocking thesis is, in short: All of history stems from the conflict between two ancient cults whose origins are obscure. Both cults worship a single female goddess, their rites are broadly similar, and their members are exclusively upper class men; the only real difference between the two goddesses is that one cult believes She is a brunette, and the other says She is a blonde. The men of these cults had hair of all colors, and bafflingly many came from areas where brown and blonde hair is uncommon or nonexistent; perhaps it was the seemingly fantastical nature of these colors which entranced them so. In these places, their wives and daughters sported any hair color as well, but where these colors were common, the women of their families were selected for either blonde or brunette hair and kept none the wiser regarding the greater significance of their locks (an almost stereotypically male move) — although this was far from universal, as I later learned to my dismay.

I must confess to finding this dryly funny. I was familiar with the tired jokes about blondes and brunettes (my father being fond of them — oh, how I fervently hope he’s not involved) , and the idea that these jokes had their origin in some battle between two antique mystery cults seemed so ridiculous I presumed the whole thing an elaborate forgery, a prank by idle gentlemen with too much learning. Yet it all seemed perfectly real: the mutual loathing was too strong for it to be a total forgery, and what is more, the whole simply made sense in some ineffable way. There is so much stupidity in the world that the idea that our rulers are motivated by something this apparently silly cannot be fully discounted.

Only a page past the introduction, my blood ran cold, my veins filling with ice-crimson. There they were, in a perfectly, elegantly lined lithograph: on the left side, the entwined snake-women from Cheyney’s letter; on the right, the back-facers of Charlotte’s necklace. The former was, apparently, the sigil of the brunette cult, and the latter the sigil of the blondes. I immediately realized two things: one, that Cheyney, Stillman, and “Him” were all brunette-worshippers, and two, that Vanderlip — and more importantly, Cynthia — were, in in the former’s case, a blonde-worshiper, and in the latter’s, came from a family of them. How on earth did they know? And why? Was there anything nefarious here? Did she even know? Was I the idiot, and her the genius, the crafty Southerner who played dumb for my stolid Yankee brain while stealing my heart for these people?

With each passing day, my horror and fascination deepened. This book was a zibaldone cataloging in wide-ranging detail an alternate history of humanity: gaudy color plates reproduced wall paintings from Luxor depicting lines of animal-headed gods kneeled before a straw-haired woman; post-mortem denunciations of Sulla declared him “a degenerate with a taste for the chestnut-streaked head”; clashing rumors regarding the Knights Templar initiation ceremony whispered of either the “blonde trollope” or “browne idoll”; pamphlets decrying Aaron Burr’s alleged conspiracy claimed “his most devilish plan would have ended in the flaxen goddess’ shadow engulfing the land”; missionary reports from Vancouver Island tell of a Coastal Salish medicine man who “warned us of the bloody-mouthed yellow-and-brown-headed-women enthroned in the central mountains”; and intercepted telegrams from “the recent war” where German officials boasted that “the Russians are fatally undermined by the brunette infiltration of their officer class.” I copied vast swaths of the book into several fat notebooks — notebooks which are now sadly lost, notebooks whose existence could have led to revolution and brought about Armageddon; I cannot tell whether this was a tragedy or blessing.

By Friday, I had read the entire book cover-to-cover, staying late each day and claiming the Cheyney papers required significant reorganization (completely true, but I was doing nothing to change that — quite the opposite, honestly). As I turned the corner behind the library, three men roughly grabbed me and pinned me against the wall. One — dressed in a seventies-era leisure suit — held down my right arm; the other — wearing a flat cap and sporting a heavy Turkish accent — held down the other. The third — a man around my age with brown hair in a green t-shirt and khaki shorts — turned and faced me, with thin, pursed lips and glowering eyes.

“Did you read the book?,” he barked.

“W-what book?,” I stammered stupidly.

“You know very well which one.”

“Well, I read maybe a few pages, no more than fifteen or twenty, tops.”

“Fucking liar! You read the whole goddamn thing!”

How did he know? Was he watching me? Why didn’t I see him?

“Listen, I was only curious. I don’t know who you represent…”

The Turk and the Man in the Leisure Suit snickered at this, but a quick sideways glance from a stone-faced Man in the Green Shirt ended their mirth. I noticed the Turk wore a ring on his left finger with the blonde cult sigil engraved on it.

“Forget what you read. Forget everything you read. It’s ninety percent outdated, anyway,” the Man in the Green Shirt snarled. “You understand me? Everything. Let him go, boys.”

“But if the information is outdated, what’s the harm, anyway? What will happen if I keep going?”

The Man in the Leisure Suit turned slowly, a smug grin crossing his face. He opened his mouth just a sliver and sang in sotto voce:

Walk on, walk on,

With hope in your heart

And you’ll never walk alone

You’ll never walk alone

Far from putting me off my project, these threats only redoubled my resolve. If what I was looking at was truly as dangerous as claimed, then I could be making history, too! My hubris blinded me to just what I was doing. The genie bursted from his fine brass lamp, and he was ready to spirit me above the sands and villages to my death.

As it turned out, Cheyney’s boxes were far from the only material in the library regarding the twin cults; indeed, information flowed to me from all directions. Books on Renaissance Italy claimed the notorious Pope Alexander VI performed bizarre midnight rituals involving women wearing brown and blonde wigs; cultural histories of twenties Paris mentioned the “Brunette Bistro,” a cheap restaurant run by an exiled Austrian aristocrat and frequented by Left Bank Americans (said Austrian disappeared during the Fall of France; rumor has it he was murdered under the express order of Hitler — speaking of blondes brunettes and…); the 1977 issue of the Journal of Hellenic Studies contains an article by “Otis Randolph” of Stanford University discussing “riots against blondes and questions of identity in Euthydemid Bactria” (I could not find anyone by that name teaching at Stanford in the late seventies; whether “Otis Randolph” is a pseudonym or a completely fictitious figure remains unknown). My notebooks piled up until they became positively mountainous; my co-workers exchanged mere pleasantries with me before hurrying off in mild terror, while the librarians eyed me warily (or did they? I do not know; the fevered mind cannot be trusted).

Their creation myths were stomach churning, full of flayed skins, boiling seas, cosmic battles between ignorant armies clashing by night, and the heavens falling to earth. Sometimes the twin goddesses were one but split violently from one another; other times, they created the cosmos through mutual combat, the shining stars and flaming comets they hurled at one another falling to earth and becoming mountains, their blood flooding the world as the oceans, the moons they destroyed shattering into millions of pieces and turning into people on the loam below. The idea of these seemingly upright men in jewel-studded crowns and starched collars believing so whole-heartedly in these awful legends made me ill, the kind of deep sickness one feels when the scales fall from their eyes and something hidden reveals itself in all its gory detail.

Walking to my off-campus apartment one bright Friday afternoon — the weather finally broke — I felt a dark force creep behind me. Sure enough, it was my three “friends” from earlier — the Turk, the Man in the Leisure Suit, and the perennially aggrieved Man in the Green T-Shirt. They took me into an alley behind our corner dive bar and shoved me against the wall; I could feel the moisture of unpleasant liquids seeping into my shirt.

“What did I fucking tell you last time, worm?”

“I mean, well, I had some projects for my courses, and —”

“That is one of the most incredibly bald-faced lies I have ever heard. We know what you’re doing. We’ve got men on the inside. When you check out a book — when you access a database — we are there, and we see you.”

“Oh, okay, I promise next time —”

“There may be no next time. You will cease this.”

“Maybe we should makes him silent right nows,” interjected the Turk.

The Green T-Shirt Man glared at him. “No, we’re not going to do anything to him. He’s ambitious, not a moron. He knows he’s gone too far. Don’cha, Linus?”

I nodded my head stupidly. “Good. Now just go back to work. Go back to ferrying rotten old papers to quasi-autistic ph.d candidates. No more independent study periods, you hear? Let him go, boys.”

A visibly displeased Turk and Man in the Leisure Suit roughly pulled away from me — hard enough that I nearly fell into a pile of trash bags. I steadied myself against the wall, my hand coated in grimy ooze.

The sun burned high in the sky, but my blood was ice cold.

The following Monday, I was disturbed from my work servicing a graduate student on the verge of collapse by a tap on the shoulder from my co-worker.

“Highsmith wants to see you,” he gravely intoned.

Highsmith, of course, referred to Chief Library Thomas Highsmith, a short, plump man in his early sixties, perennially clad in elbow-patched jackets (even when the mercury hit ninety) and a pair of thick-rimmed black glasses. Something about him always felt odd to me: he seemed like the most owlish, soft-spoken little scholar on the surface, but he had an air of mild menace for reasons one couldn’t quite name but instantly intuited.

I entered Highsmith’s office, a drab affair with off-white walls and piles of books and papers he never bothered categorizing encroaching on an old computer modem. I prepared to sit down in front of his desk when he held up an open palm.

“That won’t be necessary,” he said, smiling weakly. “This will only take a minute.”

My stomach tightened. I met his gaze but couldn’t help looking at the shiny gold pin on his tweedy lapel.

It depicted two entwined women.

“I’ve spoken with the staff, and they’ve expressed…concern about your behavior recently. You don’t appear all there, and you’ve been brusque with our researchers. We decided at our meeting yesterday (Which meeting?) that it would be a nice idea if you, er, took a break.”

“You’re letting me go?,” I gasped.

“No, not letting you go per se, just putting you on indefinite leave. Maybe next semester we’ll reconsider.”

I looked over to his computer monitor and saw old vacation snapshots with his wife and his daughter’s high school graduation portrait. Unsurprisingly, they were all brunettes.

“Listen, Linus — I understand what you’re going through, I really do. I, too, was very curious about the world when I was your age; so was my father. It’s natural. You’re in your prime right now, and everything appears free and easy and open. But there are some questions with no clear answers, ones that maybe shouldn’t be asked in the first place. We have a sense of duty to those around us, you know.”

He rose and led me to the door, giving me a friendly pat on the back. Then he leaned in and whispered:

“We’re doing this to protect you. We’re on your side, Linus.”

That night I got completely plastered at the neighborhood bar; by the end of the night, my head was positively glued to the bar, tears soaking into my arm hair like a murder victim’s blood seeping into a carpet. I was dragged out by the burly, pig-faced bartender right at closing time, the only other soul left in the now completely deserted dive. I walked through the grimy nighttime streets and entered my crumbling art deco apartment building, wobbling up the old stairs before crossing the sticky linoleum hallways and tumbling through the door into my gloomy room. I flicked on the lightswitch and found the place in complete disarray. My bedsheets had been torn away, my clothes laid in three or four sloppy piles, and my books were scattered all across the room.

I noticed, too, that my notebooks were missing.

Right on my computer desk (mercifully, my laptop had not been stolen or destroyed, although it had definitely been searched for any incriminating evidence), I saw a little white note penned in elegant cursive:

These notebooks belong to us now. You do not want these. You must forget you ever wrote them, and everything you’ve read. They’ll get you for this, you know. This is for your own good.

As my madness deepened, merely crossing campus felt like trodding through a minefield. I could trust none of the men; how could I know which of the cults they belonged to, or indeed if they were even aware of the existence of said cults? Were they narrowing their eyes at me, or was this my conspiracy-addled brain running overtime? And the women — my God! I had to avoid the eyeline of every blonde and brunette in my path. For a time I sought the company of redheads and the raven-haired, but my paranoia resulted in stilted dinnertime conversations followed by mindless rutting. There was something truly depressing about my revelations: all the millennia of cross-legged Buddhas and blood-flecked crucifixes, of hammers and sickles and the Almighty dollar, of popes and presidents and emirs and emperors — all of it was a smokescreen for a nearly prehistoric blood feud which was, in essence, an extended “blondes versus brunettes” joke.

On yet one more sleepless night after another pleasureless hook-up, my phone lit up with that familiar, sickly blue-white glow, an echoing ping disturbing the silence of the cold blackness around me. Sweatily, hesitatingly, I got up and glanced at it.

It was a text message from Cynthia.

hi there, long time no see ! i know things didn’t end super well between us but this guy told me he’d like to meet you and i should come along. he said something about you being in trouble and i could help ??? weird ! meet us at the uqbar cafe tomorrow afternoon

It was pouring and balmy that afternoon; indeed, the weather exactly matched that of my fateful discovery while rummaging through C. Hamlet Cheyney’s box. The Uqbar Cafe was sparsely populated, each table decorated with dusty vases crammed with moth-eaten artificial flowers while bluebottles flew lazily across the room. A young woman who resembled a red-haired Chloë Sevigny (Not a blonde, thank God!) sat limply in her wicker chair with periwinkle-bagged eyes staring into the middle distance; two Polish men played an obscure card and muttered profanities; a fat man in a Hawaiian shirt laughed uproariously at his own vulgar jokes, joined by another dead-eyed woman (Also a redhead! Is there a third cult?) and a nebbish sporting a prominent Adam’s apple which bobbed hideously as he chuckled. And there, off in a corner, leafing through a bricklike copy of Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy, was the Man in the Green T-Shirt.

I sank into my chair as Cynthia entered, her flaxen hair damp and frizzy, her face just as open and pretty as I remembered; I also noticed she wasn’t wearing the necklace. “Liney! How do ya do?,” she asked in her light Southern lilt, sweet with a slight touch of icy distance despite the cutesy little pet name. I gave her a wooden hug, a little too tight and ultimately affectionless.

“So, uh, Cynthia — that man over there, in the green t-shirt.You know him?”

“I mean, kinda. I met him yesterday. He’s really just the sweetest guy, y’know. Very soft spoken and smart. A true gentleman.”A true gentleman? Did he slam you into a wall twice? Did you meet his comrades and see how sketchy they are?

“What did he tell you, though? Like, you said he said I was in trouble? What kind of trouble?”

Her gaze was glassy, her smile friendly but strained. The Sevigny doppelganger let out a wheezing cough and the fat man emitted a vulgar chortle. The Man in the Green T-Shirt did not lift his eyes from the Anatomy.

She leaned in close, almost whispering, eyes wet around the edges. “That man — he knows my daddy, okay? And my daddy found out what you were doing in the library. He’s not happy; in fact, he’s scared. He never liked you to begin with — he said you were strange, too intense and bookish. And he wants you gone. That man over there will kill you tonight, okay? Y..you’re gonna die! I-I’m so sorry, Liney. I’m sorry.” Her voice quivered and light tears tumbled down her cheeks, before she quickly composed herself with perfect Southern poise.

I was consumed by a great hollowness. Somehow I knew this would happen; I wanted to rage at the heavens and gnash my teeths and plead before God but inside me there was absolutely nothing. I was supposed to cry and scream and all I desired was silence, the silence of a cosmos bereft of joy or meaning, only two towering goddesses smiling wickedly at what men will do for a pretty face, at what they will do to remake the world to ensure everything goes as planned, the flat men looking down at the screaming lady whose skin goes zap-zap-zap.

“It’s fine.” I said vacantly.

“Fine?”

“This is my punishment. Adam, Nimrod, Pandora, Prometheus, me. You get too curious or you bite more off than you can chew, this is what happens. I just want to know — where’s your necklace?”

“What necklace?”

“The one you said was pretty, with the two women on the pendant.”

“...I don’t have a necklace like that,” she bit off coldly.

“But you said you found it —”

“I don’t have a necklace like that.” She cleared her throat and gave me a light peck on the cheek, then whispered:

“I wish you’d kept going. You were almost there. I’ll walk you out the door.”

The Man in the Green T-Shirted exited right after us and turned towards me as Cynthia barreled off into the downpour after a terse, quiet goodbye; he carried no umbrella and wore no jacket, preferring to expose himself to the damp, his gaze burning hot and strong through the rain (I noticed he did not carry the Burton out with him). It was almost perfect in its symmetry: him, the superior force and right hand of the ancient blonde cult standing in the rain, wet hair plastered to his forehead; me, the stubborn Midwestern pseudo-intellectual who fell down the rabbit hole into the clutches of forces larger than history itself, cowering under an umbrella which gave me little protection from the showers and none at all from my oncoming doom.

“Expect me at eleven,” he said flatly.

“How will you do it?,” I stammered.

“That is not your concern.”

“Can I choose the way I go, then? Like, the method you’ll use?”

“No, not at all.”

I grew desperate. “Well, what about my family? My friends? My co-workers and lovers and everyone else I’ve ever known? What about Highsmith? What about Cynthia?”

To my horror he drew closer, his eyes just as rage-filled as before but his mouth twisted into a hideous grin. His thin lips parted and he sang — beautifully, hideously sang! — a half-remembered song from an old movie, one which I recall half-napping through with my grandparents as a child. His voice was shockingly smooth and velvety and the sheer force of his conviction overcame the tune’s syrupy melody and butchered lyrics. Out it came, hot and terrifying:

And you see Linus on the street, passing through

Those eyes, how familiar they seem

He gave your very last kiss to you

That was Linus, but he’s only a dream

“Expect me at eleven,” he repeated and turned away, retreating into the urban throng, the surging crowds of men and women and children and crying babies and pecking pigeons, the refuse of the city crowding out my murderer.

I gaze up at the clock and see it is now nearly ten. I am not particularly worried about death, all things considered; I am but a drop in a bucket, a perfectly average man among eight billion who — via a combination of precocity and ignorance — stumbled onto the greatest conspiracy in human history. A strange calm has descended on me, the kind of liberation known only to the living dead. I have with me a Mahler album and a small devil’s food cake, and these twin comforts shall be my final companions, guiding me through the valley of the shadow of death and the gauntlet of blood and tears and into the realm of the angels.