This picture is among the worst I’ve ever seen but also just perfect in its delusion and puerility

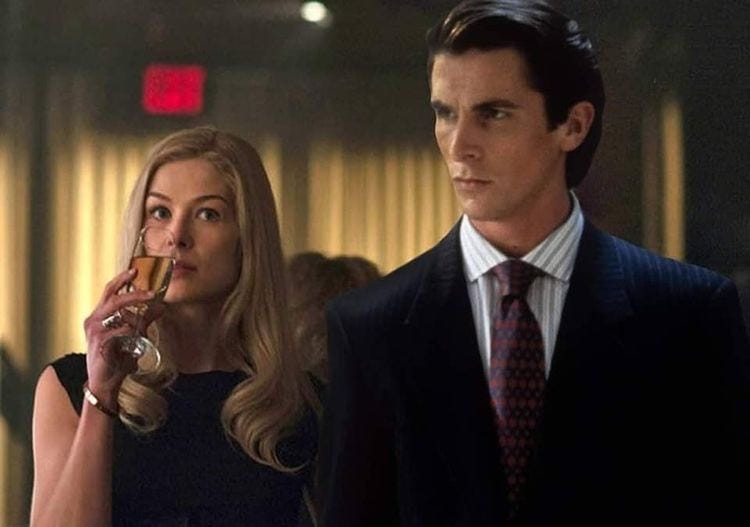

Over the past few weeks, I’ve wondered why Twin Peaks’ Laura Palmer resonated with me so much despite our significant demographic differences and life experiences. Since I’d never felt this way about a fictional character before, it took me at least a fortnight to understand she was my first “literally me” character. For those unfamiliar with the internet’s wretched underbelly, a “literally me” is a fictional character whose behaviors and personality attracts a certain kind of person, typically unpopular and suffering from an array of mental issues. As a rule, male “literally mes” are perennially lonesome and socially isolated (sometimes voluntarily, sometimes not) and attempt to escape said loneliness and isolation via acts of vengeful violence, rabble-rousing, botched romances, or all three; classic examples include Travis Bickle from Taxi Driver (perhaps the ur-male “literally me”), Patrick Bateman from American Psycho, Tyler Durden from Fight Club, Arthur Fleck from Joker, Driver from Drive, and K from Blade Runner 2049 (Ryan Gosling’s simultaneous career as chick flick pretty-boy and alienated male icon richly deserves critical study — and did Ken from Barbie thread the needle?). Female “literally mes” are defined by deliberately mercurial behavior (typically of the murderous or promiscuous sort) and the manipulation of the men around them; while this strain of “literally me” has only recently come into public view, a canon has already been assembled: Amy Dunne from Gone Girl (who in her pathetic rich kid meltdowns neatly mirrors the similarly lame and impotent Bateman), Lux Lisbon from The Virgin Suicides, Lisa Rowe from Girl, Interrupted, Anna from Possession, and the titular characters from Pearl and Jennifer’s Body.

I’ve never quite understood the whole point of “literally mes”; I guess — until recently — I’ve never had the requisite levels of alienation/narcissism to fully inhabit a character like a person rather than view them from a dispassionate god’s-eye view (or perhaps my autism is so deeply ingrained that I can’t properly express my feelings). That’s what made my over-identification with Laura so startling to me: it sent me into a volatile tailspin complete with psychological overanalysis and attempts to link disparate texts together using the increasingly thin through-line of “this reminds me of Laura in Fire Walk with Me.” I’ve never felt this with any of the male “literally mes” I’m supposed to over-identify with, even though I resent the get-out-of-jail-free “you’re missing the point if you empathize with them” shard of zoomer/millennial media illiteracy which is used as a cudgel to ignore the fact that yes, you are absolutely supposed to empathize with Travis Bickle, an emotionally broken monad wandering through the night like Cain and that of course Tyler Durden makes some correct points about the soul-sucking nature of stultifying corporate exploitation and homogeneity (even as his solution involves turning away from human connection and towards basal impulses). Similarly, none of the female “literally mes” (of whom Laura has become a cadet member) ever fully resonated, either; I, again, ended up empathizing with them and their plight (Lux Lisbon barricaded inside her house by her strict Catholic parents, Anna trapped in an abusive, loveless marriage with a particularly bitter and vicious Sam Neill) rather than feeling any kindredness.

Thinking it over, I realized why I found the “literally me” concept so confusing to me in the first place: the people who over-identify with them don’t truly like them as individual characters, but as a form of narcissistic wish fulfillment. They represent what the viewer wants to do rather than reflecting what they actually feel. If one’s stuck in a dull job or boring class or is a NEET hiding out in the basement, then the idea that you can just shoot your problems down feels liberating. There’s nothing in their lives that really parallels Bateman or Amy’s, not really (unless they’re that severely deranged, in which case they probably need professional help and not movie-watching sessions); they’re in love with the idea of just taking an ax or a pistol and ripping their world apart because that’s what’d feel good, damnit!

The idea of manipulating others as a way to offset your own anguish seems appealing — but is it really? Do you really feel for these characters or do you simply view them as extensions of yourself? If viewers were truly capable of genuine empathy, there wouldn’t be such a strong, solid wall built between each gender’s “literally mes”; the men who want to be Arthur Fleck and the women who desire likewise with Lisa Rowe do so because they don’t want to face their emotions. Doing so is painful and difficult and while the gradual release is one of the best feelings there is, it doesn’t provide the quick fix of seeing Joaquin Phoenix lead a fiery popular revolt or Angelina Jolie go viciously apeshit on Winona. If someone has a genuine sense of emotional generosity, they can see themselves in characters of any time, place, or background. This is true of cinema, sure — Roger Ebert called the movies “a machine that generates empathy” for a reason — but also of literature and theater and any other creative field. We don’t want to see through another’s eyes to obtain catharsis. We don’t want to see our own issues reflected in a distorted way that challenges us to actually confront them instead of hiding in fantasyland. We don’t want to see ourselves up there, in all their messy complexity. We want to see someone else, someone who can enact our fantasies for us, void of any genuine identification beyond the superficial “Wow, if only I was that nuts! It’s so cool to be nuts, and being nuts certainly doesn’t have consequences!” So I’m going to find a kindred spirit in Laura Palmer, despite our differences. Needing a character to be one-to-one “relatable” is a malady of contemporary discourse, anyway.